Family Life

AN UPWEY CHILDHOOD IN THE 1920's

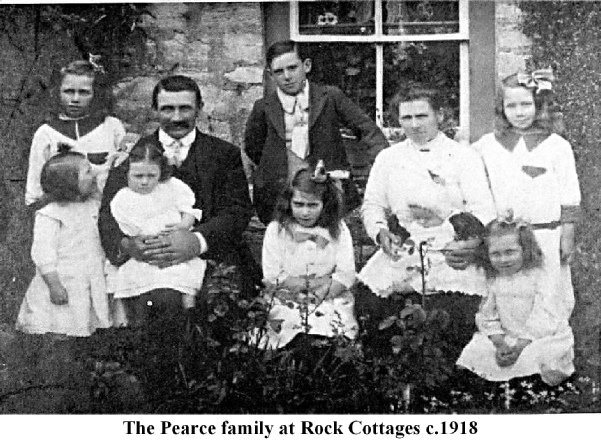

By Edith Marion Champion (Nee Pearce) 1918-

I was born at No 2 Rock Cottages, Upwey, Dorset. I am the youngest of 8 children-

My home and Garden

My father had a bad arm where a horse kicked him when he was in the South African War. He had to go away to Bath hospital when I was young to have some special skin graft. He had some flesh cut off his chest and grafted on to the back of his left hand.

It looked to me like a big pin cushion or a boxing glove. He always kept it bandaged with a roll bandage and used to change it two or three times a day, so mother had to wash them often. Father did wonderful embroidery, such as nightdress cases with butterflies, rambling roses and pansies on them. Mother was a good laundress, so much work to do in those days, with the washing and starching all the things. Old flat irons were heated in front of, or over the top of, the kitchen range. We used to love watching mother ironing the clothes so smooth. She used to sing softly to us while she ironed. She sang such old songs as "Gypsy's Warning" and "The Volunteer Organist", and she would say poetry to us and teach us different things.

We had a very large garden from the front door, which was around the back of our house. I know it sounds strange, but was right enough. The garden reached right up to Chapel Lane, which in those days was a rough lane leading to Virgin's Farm. People used to throw their rubbish in the hedge all along this lane. The hedge was a lovely wide one, and us children used to play "houses" under the bushes, sometimes in parts you could walk right through the middle of the hedge. Such wonderful "houses" we had, playing with the old things people used to throw away: Old stoves and bedsteads, pots and pans, pieces of china. We would pretend that dock leaves were cabbage, and make mud balls for meals and cakes. Oh! The kids today don't know what they're missing.

Our house was semi-

"O help us Lord, each hour of need,

Thy heavenly succour give,

Help us in thought in word and deed,

Each hour on earth we live"

There was the small push-

Mother used to take in washing to make a bit of money, as times were so hard.

In the "back house" there was an old brick copper in one corner, underneath which Mother used to light a fire to heat the water for washing and baths, and, amongst other things, cooking the Christmas puddings. The house used to be full of steam for hours at these times. There was only a shallow sink, orange it was, with one cold tap over it. There was also a big wooden mangle, and two wicker baskets she kept for folding the washing into. There were flat irons and the "back house" table with the old trunk under it, which belonged to Granddad Bird who was in the Indian Frontier War with the Dorset Regiment. That old box had travelled a good many miles, what a story that could tell. It used to be the "boot box" when I was young. We kept our wellies and boots in it. There was a cupboard in the corner by the mangle where things like saucepans, soap, soda and the boot brushes were kept. The coal was kept under the stairs, and the frying hung on the door. Coats and things were kept on hooks on the doors and the partition by the stair door. My brother and I hung ours in the corner under the cupboard by the mangle.

In the middle of the front room was a big table with a scrubbed top as white as snow. In it was a drawer where the cooking knives and forks were kept, besides other odd things. There were about six varnished wooden chairs around the table. Along one wall was the dresser where a willow pattern dinner service was set out on the shelves. My mother had worked hard for that. She cared for an old Lady who lived on the Dorchester road below us. She could not afford to pay my mother any money, so she used to give her something now and again as she was in her nineties and the only other relations she had lived up North somewhere. I have still here in my home an armchair that she gave mother. The old Lady's name was Mrs Whitby. Also on the dresser was a rosebud tea service. For that, I remember, mother belonged to a club (The Great Universal) and paid one shilling a week for twenty weeks, so she got her teapot for one pound. It came in a wooden box, all packed with straw and strips of paper. Mother belonged to that club for years. It was surprising what one could buy for a pound in those days. I still have a lovely Whitney blanket that came from there over 50 years ago and is still in regular use.

There was a tin with a picture of King Edward. Father kept his war medals in this, and it was kept on one of the shelves. The glasses were either side. The button hooks, thread needle, bottle opener and corkscrew hung on hooks, and on another shelf were cruet and egg cups of different sorts, some china ones and some in the shape of a chicken or a cockerel, which we had been given with Easter eggs in. On the bigger shelf in the middle stood the tea caddy and the vegetable dishes, curry powder pot and knife box, with knives, forks and spoons. Under this shelf were three drawers, two large with a small one in the middle. The first one was a muddle of everything from string to nails and various tools, the middle one was filled with Father's bandages, lint and pieces of rag (to tie around cut fingers) and tins of plasters etc. The other big one held the tablecloths, paper dollies, cake and greaseproof papers. Under the drawers were two cupboards, the first one held the cake tins and a big brown earthenware sugar jar, as well as flour and meat tins. It also was used for fruit and general storage. The second cupboard held pastry bowls, basins, and various plates and tins for baking.

The front door led off from the front room into the big garden. All winter this door was covered with a velvet curtain to keep the draught out. It was only opened in the warm summer days, There was a window which faced the garden where mother kept her different plants, cactus, geraniums, different lilies and of course the aspidistra. We had a goldfinch called Joey in a cage, along under the window was the sofa, which was so comfortable to lie on if one were feeling ill or tired. I spent a lot of time on that old sofa. Then there was Father's big wooden armchair, and a corner cupboard where the family bible, writing materials and different books and papers were put. On top of this cupboard stood the gramophone, with a big horn and a handle to wind it up. Next to it a pile of records, as there was no radio in those days. We had a good selection of records which my older sisters and father used to play as they fancied them. The oldest I remember were ones like "Put on your old green bonnet", "I'm forever blowing bubbles", and the old hymns, "Abide with me" and "Lead kindly light" etc. The old family bible was a wonderful book, with all the family names put in as the babies were born. It had beautiful coloured pictures in it, and had to be handled with such care. It was such a heavy book, and the pictures had beautiful tissue paper between them to keep them in good condition. The fireplace was a black kitchen range which could be opened up for an open fire, or closed. Mother did all the cooking, and heated water in big kettles on the hob. It had a big oven on the right hand side. Mother kept it so polished with black lead and the hearth white with whitening. The brass fire irons one or other of the family would clean with several other bits of brass. Saturday morning was brass and silver cleaning day, also the knives would be cleaned with a powder on a special board which hung along the side of the dresser. Along the other wall stood a large piece of carved furniture called a chiffonier which opened up and let down the front with an oval piece, with a pretty piece of material in the front. Inside this mother kept her sewing machine, a Singer, which one of my older sisters still uses to this day. Also in this place were kept all the bits of sewing, the needlework basket and button box, which we children used to play with, as it was a real treasure trove with buckles, shoe buttons, boot buttons, hooks and eyes, press studs, suspender clips and anything else one might want. Any secret parcels were also hidden in this place.

Under the table were two stools, one small for us children, the other an old chair cut off short, especially for mother to sit on to bath the babies. The lino on the floor was a lovely dark red with a sort of green and blue Paisley pattern. There was an Axminster type patterned carpet. The rugs around the floor were made of old coats and skirts, cut up in pieces and threaded through a piece of sacking. It kept us occupied for many an hour cutting up the pieces for making these. Sometimes the older girls would buy some canvas and wool to make a rug for the bedrooms. We did quite a lot of embroidery, and mother could knit beautiful lace to be stitched around tablecloths etc.

Mother used to take in washing, and when I was about eleven years old Dad bought me a bicycle so that I could go back and forth to fetch the washing for her. I had a carrier on the back and I could strap a case onto this to put the laundry in. Before I had the bike my brother and I used to go with a box on wheels, with handles to push it along. I used to go to Jesty's Avenue to a Mrs Collins, whose husband was the clerk at the mill office for Mrs Meech in Church Street by the Wishing Well. My eldest brother, Charlie, used to work at the mill at one time, and he drove a great big Thorneycroft lorry, yellow and red with B.H. MEECH & SON on it. Sometimes he would take mother and I or my brother Val for a ride out to deliver goods to Broadmayne or Preston or outlying districts.

There used to be so many stars in the sky. Mother taught us to say our prayers, to thank God for everything. The first prayer I learned was:

"In my little bed I lay,

Heavenly Father hear me pray,

Lord protect me through this night,

Keep me safe 'til morning light".

Also the Lords Prayer, Gentle Jesus meek and mild, with God bless everyone at the end. Then mother would kiss us and tuck us in tight, and blow the candle out, as in those days we had no electric or gas. We had oil lamps downstairs on the centre of the table when it was lit, and put back on the chiffonier by day. In our living room there were two big pictures, in frames, either side of the clock, containing pictures from almanacs. One was of a girl with a pretty dress and bonnet with strings. There were two kittens on her lap. This was called "Do not scratch". The other was the same girl facing a different way, with two puppies, and was called "Do not pull". They were lovely pictures. The clock was a wall clock with a glass door, which had a picture of Westminster Cathedral (sic) painted below the clock face. The door twisted open on a little catch, where the pendulum and two big weights could be seen. On another wall was a picture of Queen Victoria, also one of King George V and Queen Mary, and then there was a picture of some flags. On the mantel shelf were various photographs and china dogs and a silver plated money box with a hinge missing. I won this in a race at a Sunday school party.

My father used to keep pigs, there used to be two pigsties halfway up our garden. Dad used to love his pigs. Old Mr Guppy, the man next door, also kept them. One of his was a black boar. Father had a sow he called Sue, and he was very fond of her. I believe she was a saddleback breed. Dad used to stay up with her all night when she had her litters, and if he and mother had "Had words" (which were always over us children) he would take himself up along with Sue.

He would always tell us never to go to bed with a grievance, always make up a quarrel before going to sleep as it may be too late in the morning. "Never let the sun go down on your wrath". Father and my brothers used to caddy on the Came Down golf course. The Whitcombe family were there at that time. My brother taught me to play in the field next to us. We had our own little course, and our own sets of clubs that my brother made.

We had no indoor toilets; we had to come out of the front door and around the garden path to the side of the house. First was the coal and wood house, then the lavatory, which had a scrubbed box-

Next to the loo was a great big shed where our bicycles were kept, and Dad stored his tools and winter veg. Also, the dogs slept there in a box with straw, sacking or an old coat. Past the shed was a big water butt that stood on the corner of the house to catch the rainwater. I used to be fascinated by the different insects that lived in the water, there were some little red worms that used to come to the surface in funny jerky movements, as well as the little water fleas and daphnia.

Around the front door was a wire-

The first apple tree up the garden was one called Tom Putt, which could be either an eater or cooker. This tree had mistletoe growing. Mother's brother, Uncle Val (Bird) rubbed a berry into the tree, and after a while it grew. Then there was a golden plum tree, then the hen house and run, and then the pig sties. Up past the pigs was quite a long piece of garden until Chapel Lane. Father grew a lot of potatoes to have a store for the winter, also peas, beans and things in their season. There were several currant bushes along the side of the garden, red and black. The first apple tree the other side of the pig sties was a Beauty of Bath, a lovely soft sweet apple. Father used to save the biggest and best for the flower shows that were held each year; we had to be careful not to pick his special ones when we went for apples. There could be quite a fuss about this, and many a time Father would shout out of his bedroom window if he happened to spot us by the tree. There was another tree called a Quarentine; a dark red apple when white and pinky inside when you bit into it, lovely and crisp. There was also a Victoria Plum and a Cox's Orange Pippin. Right at the top of the garden was a bed of rhubarb and the manure heap from the pigs.

In the house at the bottom of the gate lived a family called Strange. It was only a small house, but there was a big family of four or five boys and two girls. Mr "Darkie" Strange belonged to the Upwey and Broadwey brass band, and he played a big horned instrument that went "Pom, Pom, Pom". We often heard him practising. In the next house along our drive lived Mr and Mrs Gray, Oh they were lovely old folks, especially Mrs Gray. The house was spotless and her step was always as white as snow and her brass and fireplace was a picture. You had to step down two or three steps to get into her kitchen.

Washday was a scene to behold, there were clothes lines fixed everywhere it seemed. The soaps I recall mother using were Sunlight, White Windsor, and Watson's soap, on the packet of which there was a coupon with a ram's head which we had to cut out and save to collect enough for gifts to send away for. We had clothes lines both sides of the garden reaching up to the pig sty, and a single one up past them. As well as these, lots of little things were pegged on to the wire that kept the cattle in the field next to us. I had a swing fixed up on mother's clothes post, with a piece of rope attached to one of the field posts. I was so happy on a swing. The Willis family that owned the farm by the Wishing Well had a swing on a tree at the back of their farm, which was used by their daughter Nellie. Sometimes Lizzie, her elder sister, would let me swing on it.

One year father had a wonderful bed of asters growing in the garden, and we had a picture of him in amongst them, picking a bunch of flowers. Mother had the photo enlarged and framed and hung it over the dresser in our front room. The girls used to bring their friends home from service, two of them had no homes of their own, and so when they had holidays mother let them stay at our house. There was Myrtle, a big woman, a proper "Old Maid" type; she was quite a nice old thing. At one time she went to Canada to see her brother, and one winter's eve it was just getting dark when there was a knock on the door, so Father went to see who it was. There was Myrtle in a big black fur coat and hat, with a trunk and suitcase. She had come "Home" because she was so homesick; she hated the cold of Canada. Then there was Mary Barnes, she was a maid who worked in the same place as one of my sisters. She was a nice quiet girl, and made our home hers. Mother had an old nurse friend who was a cripple and had no home. She stayed with us until she became bed-

We used to have lots of friends in those days as the girls and my eldest brother would bring their friends home for tea on Sunday evenings. Charlie used to bring Cecil Poore and Fred Lexter, and the girls their various boy friends. I've known as many as 24 sit down (somewhere!) to tea. We little ones had to have tea at the scullery table. I never liked that very much. After tea we would have a sing song and go for a nice walk if it was light nights. Sometimes we would go to the Congregational chapel up the top of our garden, where old Mr Gray would preach to us. One of the chaps that came home with one or other of the sisters was a sailor called Jim Ludbrook. My brother and I liked him a lot; he was a nice quiet lad. We played cards with him, and he could do lots of tricks. He went abroad, and brought Mother home a lovely velvet tablecloth, a wine colour, with a fawn flowery pattern on the border. So pretty it was. Then after a while he went away, and we never heard from him again.

In the autumn there were rook shoots. In the trees in the shrubbery at the back of the mill and the Well lived hundreds of rooks, and some of them had to be destroyed as they were such a pest to the farmers. So rook shoots were organized. My father and brothers went on them, and they would often bring home some of the dead rooks, which my mother had to skin to make rook pies. My father had to repair Upwey Church tower at one time, and I remember him telling us that he and the other men he worked with had put some coins into a jar, together with a letter, and had sealed them in the wall of the tower. I wonder when they will be discovered?

When I was about nine years old I was very ill with Bright's disease and dropsy. I have been told that I had 28 fits in two and a half hours. Dr Pridham and Nurse Curtis worked hard to save my life. I was off school for about eighteen months, so I missed a lot of schooling. I slept in a bed in my parents' room, and I remember waking up, regaining some consciousness, and looking around the room. There seemed to be a lot of people in the room, all the family were gathered there, they thought I was going to die. It seemed so strange, gradually recognizing each of them. As I gradually got better, people were very kind. The gentry of the village bought me all sorts of gifts; books, puzzles and games to play with. I was in bed for a long while, and had my bed by the window so that I could look out into the garden and across the fields. I used to watch the children playing, and once it snowed, and my brother went out into the garden to make a snowman for me to see.

Colonel Robinson's wife used to send her two daughters and their Nanny to see me, and often brought me some calves foot jelly or some little delicacy for me to eat. I had a little mug that they gave me for years afterwards. They also bought me a jigsaw puzzle of a ship, the St Julien, a Jersey boat. It was a lovely big puzzle made out of wood, nice firm pieces. I did it over and over again, and I knew where each piece went after a while. I loved reading and colouring pictures. Eventually I was allowed to get up, and then to go downstairs for a while. Gradually I got stronger, and when the weather was nice I was able to sit out in the garden. Then I well remember Mother borrowed the village wheelchair to push me out in.

As I had the dropsy I was enormously fat with the water around me, so I was like a fat old woman instead of a little girl. This wheelchair was very old, it was wicker, with a handle in front for me to steer a little wheel when someone pushed it along at the back. Mother used to push me to the shop. I was all tucked up, with blankets and pillows wrapped around me. All this time I was not able to go to school, and at that time we had just started with a new headmistress, her name was Mrs Dowden.

One day I had a visit from her, and after that she sent me lessons to learn so that I would not get too far behind the other children of my age.

As I got stronger I went just over the road to the market garden where the Millers lived. There was Mr and Mrs Miller and their son Billie, and Grandma Miller. She was a nice old lady. I used to help pick the fruit sometimes, and gather up the fallen apples from the orchard. They grew all sorts of fruit, gooseberries, strawberries, black and redcurrants, loganberries, big blackberries, pears and plums. I liked helping over there. Eventually I had to go to school part-

My own family

As the years went by, my elder sisters left school, and got various jobs in Service. My sister Cis (Laura) went to work in Weymouth, in Carlton Road somewhere. My sister Dorothy went to work for Miss Stokes who lived in a lovely house in Watery Lane, with a big stone wall surrounding it. The River Wey ran through the gardens, a lovely place. One of the ladies of the house was an invalid, and had to lay in a wicker pram with four high wheels. Miss Ethel, I believe her name was. My sister was the Cook General there. I remember my brother Val and I going to visit her one day. She had to kill a cockerel, to cook for a meal. We went into the kitchen garden, to the kitchen run, and she managed to catch him after a chase and a lot of cackles and clucking from the other fowls. She caught him up by his two feet, picked up a chopper and laid his head on the chopping block, and cut his head right off. She put the bird down but he got up and ran all about the garden with no head on, it was a strange sight I shall never forget. It eventually fell over, I suppose it was the nerves still twitching, very queer.

My sister Ena went to work for Alfie Symonds, in a farmhouse on Broadwey Hill.

Ena had a lovely son, Raymond. She brought him home and Mother bought him up like her own. He was about seven years younger than I was. I used to take him to school, when he was old enough, on the back of my bike, on a little seat, which was allowed in those days.

My sister Mary went to work for old Mr and Mrs Reynolds, who lived on Broadwey Hill in a house called "The Myrtles"; they were a dear old couple, I believe he invented the cheese-

My favourite sister was Dorothy. She got married to Jim Johnson when I was about eight years old, and lived in Portsmouth. Jim had a motorbike and sidecar, and sometimes came to stay for a weekend or holiday, and sometimes I went back with them to stay. Occasionally I would stay for a few months, and had to go to school where they lived at Purbrook. I didn't like it much, as I knew none of the children. Whilst in Portsmouth, Dot had a son, Charles, and a daughter, Ruth. Then another son, John. They came to Weymouth before the war and lived at 23 Hope Street, where they had another son, Robin. When the war came they returned to Portsmouth. Jim went to Egypt and never came back, so Dot had a divorce after three years and then married Jack Saunders. After ten happy years they died within twenty two days of each other.

My eldest brother, Charlie, got married to Jose, and went to live with her family in Market Street, Weymouth, where they kept a guest house. I went to stay there once, but got so homesick I had to come home. Then they moved to Southwell, in Portland, to keep a pub called the Eight Kings. I used to love it there. Jose and Charlie had a son called Peter, and Granny Dees adopted a boy called Tony. I used to spend my summer holidays there; such wonderful times we had. They had a hut out at Portland Bill where we used to spend lots of time climbing on the rocks and swimming in the quiet coves. Such lovely food we had, crab or lobsters all freshly cooked, salad and lots of home-

My Dad's sister, Auntie Millie, lived in the Rectory Cottage that stood where the Church car park is now. There was a cobbled yard for the vicarage coach and stables for the horses. Auntie Millie and Uncle Tom had about fifteen children, such a big family of boys and girls; they were all older than I was. Uncle Tom worked as a Hedger, he went around various farms cutting the hedges and cleaning out the ditches. Sometimes we would visit the family, and sometimes, if the weather was bad, we would take our school dinner to eat it there.

I remember the big kitchen, it had a big chimney corner, and had benches either side of the fire. Often Uncle would sit there on the bench sipping cider from a jar, and then, every now and again, gave such a spit in the fire, and the fire would hiss and steam. He smoked a clay pipe like those we blew bubbles with. Great logs would be laid across the fire, sticking out across the room sometimes. Often, if it was cold, Auntie Millie would give us a lovely basin of stew from the hot pot that seemed to be always hanging over the fire on a hook. The stew was usually a rabbit or perhaps a pheasant or hare that Uncle had caught while working in the fields.

Some Upwey characters and families

In every place there are some characters that stand out in memory. There was one old man who was a cider drinker, and often had too much to drink. I remember it was my birthday, and I met him with his old whippet dog. I said to him, "Hello Mr Newman 'tis my birthday today". "Oh is it my pretty dear", he said, "Then let me see if I've got some coppers for you", and he staggered back to put his hand in his pocket and gave me two pennies. ""Here you are my dear", he said, so I said Thank you very much and ran off. Well, when I met him again, I was artful and said it was my birthday again. "Ah, my dear, you have a lot of birthdays don't you?"

There was Mr Squibb, who walked with crutches as his legs were crippled with war injuries. He often sat out in the little hut that was called the Pensioners' Hut, out on the road by the Royal Oak. There was a strange young woman called Alice Thorne that used to sit in the hut with him. Then there was Fred Harris; he wore an iron on his leg, and one hand was paralyzed. He used to go with his glass to the Wishing Well to earn a few shillings from the visitors. Up Roman Road by the Ship Inn was the village blacksmith. We loved looking in the forge to see the fire glowing and the horses being shod, the sparks flying about, and the clanging of the hammer on the anvil; such a strange hot smell.

On the side of the railway line were a number of gardens that the men on the railway looked after, like an allotment. There were several by the cricket field, and sometimes my brother and I would creep along the hedge and steal some of the lovely fruit that grew in Darkie Strange's garden. There were delicious loganberries and some great big Cape gooseberries. Oh! nothing tasted quite like stolen fruit, we were very naughty. We almost got caught, but not quite. We got a good cussing sometimes.

Up by the church lived the Willis family. There were several grown up children, and twins, a boy and girl, about my age, Margaret and Jack.

The family put on a concert in the big barn that they kept the hay cart in, on the hillside going up to Gould's Hill. I well remember sitting up in a wagon with other smaller children, the big ones were in chairs or sat on boxes around the barn. They had a platform or stage fixed at one end. There was one scene, t'was all the cast with their faces black, like the Black and White Minstrels, singing "Poor Old Joe" and "Way down upon the Swannee River", we were nearly all in tears. The Willis's had a Tea Cabin where they served fruit teas in the season. It was in the garden, just opposite the top church gate. In the cottages opposite lived old Mrs Snook, Miss New and Mr and Mrs Critchell. The Critchells had some topiary in their little front garden; the bushes were shaped like a settee, armchair and table, very interesting.

Down the road from the school, a little way on the left, past Wabey House where Mr Meech lived (The man that owned the mill) was another Tea Garden, which the Clark family kept. There were some big red painted doors, which led into their garden. The "Brakes" stopped there sometimes for visitors to take tea.

Mother used to take us gathering blackberries. We took a picnic tea to Bincombe Heath... There used to be a lovely wood with fir trees right at the top of the hill (Note: Culliford's Trees), where we would find a mossy dell for our picnic, and afterwards gather blackberries. There was a lovely lily pond close by where we watched the frogs on the lily pads, and picked rushes to plait. We walked miles looking for mushrooms, and went to the fields where we knew they grew. It was just like hide and seek, such a thrill when we found some. My brother Charlie used to go to a house in Laurel Lane, by the Royal Standard, where a Mr Trump lived. Mr Trump made lovely Chesterfield sofas, and my brother learnt how to make them, and when he got married, Mr Trump made a settee and two armchairs for their home. I used to go up to the house, next door to old Mr Woodward, with Charlie. Mr Woodward had a married daughter, and she had a little boy I used to play with. I got on better with boys than girls.

There were two brothers that lived in the Royal Standard, called Peter and Paul Hyde, I played with them quite a lot. They had a wigwam tent in which we played Red Indians, and I was their squaw. Once we had the tent in the field, and one of my sisters took our photo as the train went along the line in the background; it made a good picture.

There was a friend of mine, a little older than me, Gladys Strange, she lived in Rose Cottage, Prospect Place. I used to love going to her house. We always called her mother "Aunt Maud". She was a tall thin lady who wore her hair parted down the middle and tightly brushed back into a bun.. I was very fond of Aunt Maud and Gladys. They had a lodger, Mr Geddis, he was a big man who usually wore a navy blue suit and a Trilby hat, and walked crippled, stiff legged, and used a walking stick. When he was away on business I used to sleep at their house for company, sometimes with my sister Winnie. At night-

In Stottingway House there was an old couple, Mr and Mrs Gray. They came to live there after the Hildebrand's died or left the village. Mr Gray used to have a little Bible Class on Tuesday evenings, and several girls used to go. I went along with Edith Didcock. We used to have hymns and Bible readings which were then explained to us. Then we had a drink of tea or lemonade, and then prayers before going home. We used to visit the different places of worship which we liked. There was the village church, Upwey St Laurence, the Wesleyan in Elwell Street (now a house).

In Church Street, near Eastbrook field there was a little Primitive Methodist Chapel, which is also now a house. Then the Congregational Chapel at Chapel Lane, at the top of our garden, where old Mr Gray used to preach. He was a lovely old man with snow white hair and preached lovely sermons. Margaret Longman used to play the old harmonium. Mr Gray's son, John, was a tall handsome man with a lovely strong voice when he sang. We used to have lovely Christmas parties and concerts in the schoolroom, and cookery classes were held there on Thursdays. Father could see into the room from our garden. He refused to let me go to cookery class because the women used to smoke while teaching us. Father told that Mother could teach me to cook better than that. So I went to school while the others went to cookery.

A girl I used to play with a lot was Doris Howley. She had a brother, Tony. Doris and I used to play at table decorations. Mother would give us a bit of old lace curtain for a cloth which we used to cover an old box or stool, and went into the fields to pick wild flowers to decorate our tables. Wild parsley, buttercups, clover and daisies were some of the flowers we used. We put them into little paste jars filled with water. Mother or somebody would come along and judge what we had done. I remember once Father saying we could have the old chicken hut for our play house if we cleaned it out. So we gave it a good scrubbing and whitewashed it inside and out. We had lots of fun in this playing shops and houses.

School and Church.

Sundays were lovely days. I went to Sunday school with my sister Winnie and Brother Val who was in the choir. Dad and Charlie were in the choir when I was very small. We children used to sit in the pews over to the right of the church, and I well remember old Colonel Bland used to sit in the centre pews opposite us, by a big stone pillar. He used to bring his spaniel dogs to church, two of them, and these dogs would lay so good under the seat. The old chap would lean against the pillar and would often nod off to sleep and start snoring. My brother sometimes had to pump the organ as at that time they had to pump the bellows. He used to sit on a stool behind a red curtain.

The first schoolmistress I remember was Miss Nix. The headmaster was Mr Smith, he was a stern man, but very kind and fair, and there was Miss Mallard who used to teach the" middle" classes. I well remember sitting in the Infants' room at our little desks, pulling the threads out of little pieces of material, "picking out" we used to call it. Why we picked out I never knew, unless it was used to stuff toys or dolls. We also had counting beads on wires. There was a glass case with some snakes in a bottle of spirit or something, some stuffed birds, a squirrel, and a model white cow on wheels. The South Dorset hunt used to meet outside the school occasionally and we were allowed to watch the riders in their red coats and the ladies in their riding habits, and the Master of the Hounds, with all the dogs around him, calling them all by their names. Once they killed a fox outside the school, and I was horrified when they cut off the brush and gave it to my sister Winnie, as she had the same red hair. Winnie wore hers long, almost to her waist, it was lovely!

She had a very quick temper which goes with folk with red hair, they say, but she was the thriftiest of our family. She went to work with a Miss Kindersley at Broadway, and if she made a mark or spot on the tablecloth she had to put sixpence in the missionary box.

When I was about five I ran away from the Infant's class as one of the girls, Lily Trevett, said I had stolen her handkerchief as she had lost hers and I had one exactly the same. The teacher took mine away and gave it to Lily. I was so upset I made to go out to the lavatory, and then ran on home, which was about a mile away. Several people asked me where I was going as I was on my own and crying in the road, but I ran on till I looked around and saw my sister Winnie, together with Violet Mills, running after me. I ran on to the field called "Newclose", where Mrs Wakely was hanging her washing out on a line across the field. She tried to stop me but I ran and hid (as I thought) in the long grass, then when my sister came Mrs Wakely told her where I was, so they picked me up and took me back to school again. Mother wrote a note to the school next morning that memory lingers clear.

I remember the teachers changing. Miss Lunn from Martinstown took over the Infants and Miss Ida Rogers took Standards 1 and 2, and Mrs Dowden was the Headmistress. They were there till I left school. We were all very fond of our teachers, at least I look back on them with fond memories. I know my sister Win and Miss Lunn were very firm friends and often we used to walk back to Martinstown with her after school. We used to walk miles in those days and think nothing of it.

Miss Ida Rogers was the teacher at Upwey School for Standards 2, 3 and 4. She used to take the girls for sewing, and I hated sewing. I remember making some white calico knickers. I don't know what happened to them when they were made, I know I never wore them. There was an examination of our work and none was more amazed than I was when I won a prize for sewing!. Such a pretty little round pink work box, with a string of pink ribbon to keep it closed. It had pretty pink roses on it. I think it must have been for encouragement rather than good sewing. Goodness only knows what the rest was like if mine was the best.

At school we had no dinners like today, we hurried home a mile away and had a good cooked dinner if the weather was good, but if it was wet and cold we took sandwiches and an apple or orange, and had a cooked meal when we got home. We used to sit in the Infants' room with Miss Lunn. Sometimes we would take an egg and she would boil it for us in a little saucepan on the open fire that was in the corner of the room. In the other classes were big black stoves that burned coke (Sometimes the fumes were bad). They each had big strong fire guards around them. The cleaners of the school were Mrs Wills and her daughters, Evelyn, Linda and Violet. They had a brother Bill a little younger than I. Mr Wills used to work at the mill with my brother Charlie, but he died while I was still at school. The toilets were across the playground. There were wooden seats and buckets, as there were no flush toilets in those days. The coal was kept in the same building, a door on the side. The boys' toilet was around the back of this building, along a passage, the front part of which was the boys' cloak room, where they put on their coats and hats, the girls lobby was around the other side of the school building by the Wishing Well, with a door into the Infants' class leading off it.

A person used to visit the school to see that our heads were clean. We used to have to line up and wait our turn to go in. We sat down on a chair, and she would stand behind and go through our hair, prodding and pulling to see if it was clean. Several children had to be sent home to have their heads washed with carbolic soap, to get the nits out of it. Thank God, ours was always clean! It must have been very humiliating for the kids who were sent home. We played with hoops, round wooden rings about an inch thick, nearly as tall as ourselves, which we wheeled, or trundled along with a stick My brother had an iron one, and trundled his along with a hook thing, skipping with lovely long ropes held by someone at each end, and someone jumping in and skipping as long as we could. Marbles, Hop-

At school there was only a small playground, and at playtime only the infants played there. The biggest ones played around outside or went up School Hill, which was very hilly, where we played roly-

Once, after I got my Wellington boots, several of us children went paddling in the river by the school, where the water runs under the road through a low tunnel.

I remember looking up it, and deciding to go through. It was very dark. I was a very small child, and I didn't have to bend down until about halfway through. Suddenly the water got deeper, and I tried to turn around to go back, but the water was flowing against me and it was harder, so I went on through this dark tunnel, and the water was coming over my boots. Anyway I got through the tunnel and found a crowd of children waiting for me, together with the teacher, Miss Rogers. She was all red in the face and worried that I might have drowned. I never realised at the time that I was in any kind of danger, but when I think of it now, the tunnel was so small that no grown-

I think I must have been a problem child at school as I got older. I remember once our class had been given new exercise books, and we all cut a slice off each corner. When the headmistress saw it she was very cross and wanted to know who started it. Well, I thought, she mustn't hit me because I've been ill, so I said that I'd started it. She replied that the others should have had more sense than to copy me, and we were all kept in for playtime. Oh, dear, we didn't like that very much!

Mother had a step sister who lived in Portland, Auntie Sue, she was a teacher at a Sunday School in a Chapel just behind the Chesil Beach. Sometimes their Sunday School would come to Upwey for their summer outing. My mother would get the Tea for them. They got permission from Mr Baker to use the field near our house to have games and races and their Tea. My brother and I thought we would make ourselves some money. We went to the market garden (Sticklands in Prospect Place) and bought some apples. We got a big basket of "Fallers", and took them to the children, selling them at ten a penny. We did very well, and soon sold out. So we went back to get some more.. "Oh!," said Miss Stickland, "You soon got rid of those, whatever have you done with them?". Well, quite innocently, we told them about our little business, whereupon she would not sell us any more, so that was the end of our enterprise!

When I was very young I remember the Sunday school children going to the Vicarage after Sunday afternoon school to hunt for Easter eggs, which were on trees surrounding the lawn. It was lovely. We used to wear lovely Easter bonnets, straw ones with primroses, rosebuds or daisies on them. So pretty they were. At Whitsuntide we wore white dresses, gloves, socks and shoes. We all thought we looked very nice. We were given lovely texts, and celluloid crosses with flowers and pretty pink tassels on them. Oh, such happy memories.

Several of the Foot family were Sunday school teachers, and every Christmas they gave a lovely party in their big house opposite the mill. We used to take clean pinafores to wear over our frocks, all neatly starched. Once, when I was in the Infants' class at school, when Miss Nix was the teacher, she asked those who were going to the party to put up their hands. I was collecting pencils or something and did not put up my hand, and when it was time to go early from school to the party, I got up to go out with the others, and teacher made me sit down in my chair, as I had not put up my hand. I was so upset, and I cried. Teacher said I had taken too much for granted and kept me back for five minutes. I remember going to the house all on my own, crying my eyes out. I remember Miss Hilda was so kind to me, and took me to wash my eyes and tidy up before I went in with the others. Oh Dear, what a lesson!

Out and about in Upwey

"Westbrook" is one of my favourite places in Upwey. We used to play hide and seek around the barns and sheds, up in the hay-

In Hurdlemead, the field we crossed on the way to school, there was a ditch with water in it. In the ditch, or on its banks, grew many different wild flowers, one of which was meadowsweet. Mother used to say it was her favourite flower, so we often picked her some as we went home when it was in flower, usually in full summer. It smelt so sweet, sometimes we ate the flowers. The bottom end of the field by the Mason's Arms was always marshy, and there the Kingcups, cuckoo flowers and anemones grew so pretty. In the hedge nearby were several damson trees, which we loved to pick when they were ripe. Frankie Bowditch used to keep sheep in the next field, but that is now built on, a market garden I believe.

In Bottom Plot, behind the houses, was a stable and sheds where Mr Trevett the coal merchant, used to stable his horses and keep his coal cart. There was a lovely hay loft there where we used to play with the children in the nearby houses. There was the Butcher family, Grace, Dick, Dorothy and an elder sister, and the three Boalch girls, Kathleen, Valentine and Barbara. There was a small wood where we made a den. We played cricket, rounders and football in the field, as well as French cricket and hide-

Upwey and Broadwey Cricket Club had a cricket pitch in Mr Virgin's field in Chapel Lane. On Saturday afternoons Jean Hart and I went up to the big wagon barn to help Mrs Johnnie Walker to get the teas ready. We laid up the trestle tables with cups and saucers, and put out the milk and sugar, together with fancy cakes on plates. When the teams had eaten their tea, we got any cakes that were left, and helped with the washing up. Tea was made with some kettles boiled on a primus stove, and the tea made in a big urn. We washed up in a big galvanized bath.

In the field called Newclose there was a red galvanized building against the high wall of a Nursery (I believe someone called Mr Warr kept the Nursery). This horrible building was the reading room. I think it must have been a Library at one time. Whist Drives, parties, wedding receptions and other functions were held there. Up in the top corner on the right of Newclose used to be a walled in rubbish tip. My brother Val, sister Win and I went there once, sorting out rubbish. Win found a three pronged fork and Val a silver spoon. When we took them home and cleaned them up they were always called Winnie's fork and Val's spoon and were always set at their place at the table. Many a squabble was had if they were put out for anyone else. There were lots of public footpaths in the fields around. There used to be about four different paths across Hurdlemead that lead from Prospect Place to Church Street or Elwell Street. There was also a path from Hurdlemead to the field called Plot, that led through two fields to an outlet between the Primitive Methodist Church, and Eastbrook field where Miss Symonds lived. Once my brother and I went that way, and saw some holes in the wall which had some gauze stuff over them, about five round holes in the shape of a cross. My brother had a look through where the wire was broken, put in his hand, and pulled out an egg. He told me they were magic holes, so I put my hand into one of the holes, and I found an orange. Well, we thought that was a lucky dip indeed. When we got home we told mother what we had found, and later we showed her where it was, this magic hole place. "Oh My! don't you ever do that again", she exclaimed. It was Mrs (sic) Symonds larder that was our lucky dip.

In "Lower Plot" field there was a spring of water in the middle, and if any of our family had a sore eye, or a pain in the eyes, mother would send one of us with a medicine bottle to fill up with water from that place. It was all sort of rusty in the bottom, and was supposed to have healing powers for bathing eyes. I don't know that it did any good. Mother and father bought spectacles from Woolworths for sixpence a pair. There was no National Health in those days; we used to pay in a sick club for the Doctor.

My grandfather Bird (note: Richard Bird (1839-

In the spring we used to go gathering primroses from Ward's copse, which was across the fields from Westbrook. Such a lovely wood with anemones, bluebells, primroses and wild orchids (which we called Granfy Giggles) growing there. A few years ago it had vanished, it had all been cleared and it was just a green field when we visited it. It was so disappointing. Which reminds me of Virgin's copse. We used to go through the railway bridge up to Virgin's farm and go to a small copse just before the hill we called "Lookout". (Note by MJE: this would be the hill where my mother, Laura, said they walked to with the school in 1910 or 1911 to watch the Fleet Review in Portland Harbour). Mr Virgin would always tell us not to walk in the wood as there were some special birds nesting there. Well, one day my brother and I went along the side of the copse picking blue, white and mauve violets, when we came to a gap in the hedge, so we had to have a peep inside. The flowers were lovely, primroses and daffodils, all kinds, so we said we would pick a few. Well, we gradually got further into this wood, when we suddenly came to a grave with a little wooden cross, with flowers in a jam jar. Quite a big grave it was. We children went home with our flowers and told Mum and Dad where we had been. We got a good telling off, but they were quite interested and said it might be a pet cat or dog, but anyway not to go again. Some time after my Dad told the village policeman, Mr Smithers, what we had seen. He made an investigation, and it was found that the Virgin children had a pet pony called "Snowball". When their old friend died they didn't want to send him to the Knackers Yard, so they buried him in the heart of the wood, which was a nice thing to do.

The Wishing Well Tea Gardens were kept by some people called "English", when I first went to school. It was beautifully kept, and out on the garden lawn were some lovely swings. Now I loved swings when I was little; put me on a swing and the world could roll by. I was so happy I could have lived on one. Sometimes, when my older sisters were with me, they used to pay a penny to have a swing. We took sandwiches for dinner and ate them all during our dinner hour, where we spent the whole time. Out in the Wishing Well, which was not only reached through the garden then, but by a path which led to a kissing gate in the corner wall, one had to be careful on wet days because the farmer's cows used to come and go from Windsbatch Hill to the farmyard over the road to be milked. They made an awful mess of the path, but the visitors came just the same. Several old age pensioners, handicapped people or widows went there with a few stemmed glasses, filled them up with water from the spring, stood with their backs to the wall, drank and wished, and threw the remainder over their left shoulders back into the well. Many a person got splashed, but it all added to the pleasure.

Once a big tree from the shrubbery at the back came down in a gale, and people used to climb on this to have their photograph taken. The people giving out the glasses used to get tips for their trouble and it was "perks" for them, but now it is all commercialized and you have to pay as you go through the shop. The Prince of Wales came to the Well when I was small and we children stood up on the parapet with our Union Jacks up in the shrubbery singing "God bless the Prince of Wales"

After the English family left the Tea Garden at the Wishing Well, Mr and Mrs Davage took it on. They had a daughter, Christine, who was a year or two younger than me. She came to school with us. On October 1st, her birthday, she used to have a party in the Café. We had great fun playing party games, and a lovely tea.

Shops and Tradesmen

The postman was so smart with his round peaked cap and navy blue suit with red piping around. Mr Baker, with his big baskets, was the baker; the field next to our house belonged to him. In his shop they sold cake, bread and pastries with just a few chocolates, groceries and sweets. This was on the Dorchester Road; I believe it is Smiths now. In Elwell Street was the Post Office, where Miss Corbin and Miss Dunn served behind the counter. Then there was the milkman with his cans of milk, which he ladled into our jugs with either a quart, or a pint, or gill measures. Alf White was the milkman who worked with Ray Rogers. The butcher was Butcher Gould or Frankie Bowditch in Elwell Street. He used to frighten me, because the shop was just a sort of passage and large hooks and things hung from the swing thing with great carcases of beef and lambs. Frank used to shout like anything when he spoke: "How are you, Miss Pearce-

His old father was a gentle old man, I was not afraid of him, and I was very pleased when he served me. Frankie's sister would sometimes be there. Up over Little Hill was Mr Burden's market garden where in the summer they served fruit and cream teas on the lawn. There was a Monkey Puzzle tree in the garden. I remember Jack and Jean Burden came to school at Upwey. Their mother and father and grandparents, old Mr and Mrs Burden, were lovely old people, I liked them a lot. We were sometimes sent there for tomatoes or strawberries and other fruit in season. Then down on Elwell Street below the Post Office was old Granny Trevett, wife of Coal Merchant Trevett. She used to have a little room where she served Teas and ice cream. On certain days she would make faggots and peas and black pudding, and on Good Friday she would make "Fermitty". Mother would send us out with a basin to get some. Further down the street was Barbers, the grocers, and before that at one time there was a fish and chip shop. In Barbers there were old Mr and Mrs Barber and their daughter Queenie, and then further on down was a big walled-

There were several pubs, one of which has gone, the Royal Oak at the foot of Ridgway Hill, which had only a six day licence; they closed on Sunday. There is still the Royal Standard, the Ship Inn at Ridgway, Roman Road, and the Mason's Arms in Church Street.

Then I remember a Mr Blackmore, the Packman who used to come every now and then with a big black suitcase which had everything that mother needed for sewing and mending; cottons and buttons, hooks and eyes, ribbons and tape, elastic and binding, and he would also have overalls for ladies. Aprons, socks, men's and children's, ladies stockings and underwear. We children loved to look inside his case. Then most weeks old Mr Cox would come from Weymouth with his horse and cart with the oil for the heaters, stoves and lamps. Father used a lamp that burned some stuff called carbide and oh! HOW it smelled that bicycle lamp-

Near our house, along Dorchester Road, was a little Newsagent's shop where the Trevetts sold papers and cigarettes. Then it was changed to a Boot and Shoe Repairers, where a man called George Vallance worked. There were some people called Westlake in a market garden across the road from where we lived, and another big garden with flowers and fruit kept by Mr Palmer on the top of Stottingway. It is all built on now. Then at Gray's corner was the millinery and haberdashery store (K Wright), Grays the grocer and Goulds the butcher. The Broadwey Post Office was in Old Station Road. There was a Chemist opposite the butchers', then on Broadwey Hill was a little shop where Mr Chalker sold oil and groceries, and further down the hill was Newman's the shoe shop where Mother took us occasionally to buy plimsolls, socks and shoes. I remember having some lovely black patent ankle strap shoes from there when I was small. Mr Johnny Pegler was the Headmaster at Broadwey School, halfway down Broadwey Hill. He was a short fat man with glasses. He was very strict, we were told, and often gave children the cane. Then there was another little grocer's shop by Symond's Farm opposite where the Wesleyan Chapel now is, and then the Swan Inn at Broadwey.

There were several postmen, old Mr Baggs with only one arm, Jack Wills who lived just below us in Dorchester Road, Mr King, Mr Tidby and dear old Neddy Lovelace, who spoke very broad "Dorset". If the weather was foggy and wet he used to say, "Tis zardalike voggy ondervoot s'mornin me dear". There was the lovely smell of the Mr Baker's bake house, just off the Dorchester Road. I often used to peep inside the back door and see Mr Baker, his son Dick, and Mr Trevett and Eddie Carpenter busy making up the dough. They wore such lovely white aprons and stiff starched hats.

Brownies and Girl Guides

As I grew up I joined the Brownies, which was held in the old Women's Institute hut, next to the garage. We had some lovely times in this place, concerts, dances and parties. Our Captain was Miss Alice Mayo from Coryates. We had such lovely times on tracks, campfires and jamborees. I remember being a Standard Bearer with Edith Didcock and Christine Davage at Kingston Park, Dorchester, and we had to present the flag to a Princess, I forget who now (Note: See below). Edith was to be my friend for many a year. She lived, and still does, with her husband and family at 2, Stottingway Street, but as houses have been built, they are now No 13. I remember her mother was very sick, and died when Edith was about ten years old, so she had to be "Mother" to her father and two brothers. They had a lodger, Reg Mayo, who played the trumpet in the local band, and Edith had an organ that you pedalled with your feet to blow the bellows, to make the music. I learnt to play "Now the day is over" on this.

My sister Winnie was in the Girl Guides, and when I was old enough she took me along to the Brownies, which were held in the Women's Institute hut. Later I joined the Girl Guides, and made some good friends. Our Captain was Miss Alice Mayo. I enjoyed the Guides; we used to do lots of nice things. I used to love tracking and camp fires. Miss Mayo lived at Friar Waddon, and sometimes we would go from Broadway Station to Coryates Halt on the train that ran to Abbotsbury. Miss Mayo would lead us on a marvellous track, all over the hills. She would be waiting for us somewhere, and we would light a lovely bonfire and cook "Dampers" and sausages on sticks, and brew up a drink of some kind. Oh! I loved tracking. Once there was a big rally in the grounds of Kingston Maurward House (Note: the date was 1 May 1930) where the Princess Royal (Princess Mary) had come to inspect us. Christine Davage, Edith Didcock and I had to present our banner to her, and we shook hands with her. Both Guides and Scouts were there. Afterwards we had camp fire songs, it was a grand day. Guiding is very good training for life in the future; I look back with affection and appreciation for those days.

Visiting Weymouth

The buses were very few and far between, the first buses from Weymouth to Royal Oak, Upwey, had the top deck open and the drivers seat was outside with a spare seat on which, if it was fine, we used to try and sit. Mother used to take us into Town (Weymouth) with her sometimes, and when the pictures started we used to love Thursdays when Mum said, "If you are good we will go to the pictures". So we tried to be good and hurried home to tea, when she would wash and brush us and take us to catch the 5.30 motor train from Upwey Junction or Bincombe Halt to Weymouth where we would make our way to the old Market Hall by St Mary's church where mother would buy any food she wanted, and then our treat from Mr Chick and his daughter who had a fruit stall. We used to love their coconut slices, pink and white, so sweet and lovely, or their boiled sweets. No paper on them in those days. They made bags out of paper, like dunces caps. They rolled them around their fingers. There were some boiled sweets with all lovely flavours, a mint rock taste, humbugs, cloves, lemon, orange and other flavours. They also sold broken biscuits. When we had bought our sweets we went to Mr Denning's fruit stall, and buy oranges, monkey nuts, apples and bananas if mother could afford them.

From the back of the market we went to the Belle Vue picture house in East Street

Mother took my brother and me to the pictures most Thursday evenings all the year round. We used to see the commissionaire, Mr Self, outside or in the foyer. He looked very smart. He was a tall, fair to ginger man with a waxed moustache, very slim. He would saunter around with his hands behind his back, calling out the price of seats that were vacant. We used to like the back row down, right in the centre, so that if anyone tall was to sit in front of us we could put our seats up and sit on the back.

We used to follow up the serials, such as Rin Tin Tin, an Alsatian dog that did wonderful things; Tom Mix on his wonderful horse did wonderful things with his Lasso. Felix the cat was popular, as were Charlie Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy, Will Hay as the schoolmaster, and The Invisible Man. Oh such wonderful films they seemed to us. After the cinema we would come out and make our way to Park Street towards the station, where we would buy some fish and chips. If we had time we would eat them in the shop with salt and vinegar, but if we had to hurry to catch the train at 8.50 we would take them home and eat them there.

Visiting Dorchester

Sometimes Mother would take us by train to Dorchester. We went to Upwey Wishing Well Halt, on Ridgway Hill, and climb up the steep bank by the steps to the platform to catch the train that stopped at the little Halt to pick up passengers. We got on the train and bought our tickets from the Guard. The train then went through the mile long tunnel, where it was pitch black going through if the gas lamps were not lit, then come to another halt called Monkton, then on to Dorchester. Sometimes we would have a look around the Market where the animals were all in pens waiting to be sold; the pigs used to squeal something terrible. Another time we would visit our relatives that lived in Dorchester, or went on to the village of Charminster to see Mother's brother and his wife, Uncle Val (Note: Valentine Bird) and Auntie Ivy. They had five children, a girl, Evie, and four boys; Val, Alan, Eric and John. We had lovely times there playing in the fields, or by the river, or gathering nuts in season. Uncle Val had been a sailor and could tell lovely stories , have sing-

Cars and Buses

There was not much traffic on the roads; mostly there were horse drawn vehicles. Several of the "Gentry" had cars. I believe Colonel Bland had a big Daimler. It was maroon with a big hood that folded back in fine weather. It had a chauffeur and the brass shone on the big lamps and door handles. I believe the chauffeur's name was Mr Bartlett . When the coaches started to bring trippers to the seaside, they called them charabancs. They had folded hoods, from which the trippers used to throw out streamers as they rode along, and hung balloons around them. Often they would throw pennies to us children as we sat on the wall at the end of our driveway. There was a gate, a big gate that closed us off from the road. The drovers used to go to Dorchester market, to drive the animals along the roads to the various farms or butchers.

The horse-

The road menders used to work with a big engine-

Buying sweets, and Bonfire Night

Father had an allotment, up over the hill, off Friar Waddon Road, and sometimes when we were playing outside school we would see him cycling by. He would stop and speak to me and my brother, and would give us a halfpenny or if we were lucky a penny. Then we went into Davidge's Café (next to the Wishing Well) to buy ice cream or a gob-

We had a gang of children who used to play up on Roman Road, where we had a den in the bushes. We sometimes pooled our money to buy lemonade at twopence a bottle. The bottle had a glass marble in the top for a stopper, which you had to press in to open it, and sometimes we were very naughty and bought a box of matches and a twopenny packet of five Woodbine cigarettes, and have a puff at these. Sometimes we lit a fire. On Bonfire Night all the children gathered wood and stuff to take to School Hill where there was a huge bonfire, and folk let off their fireworks. The boys would cut out the furze bushes on the hill, make up the fire, and people bought stuff along to burn. Everyone was friendly, and we knew everyone who lived in the village.

The Upwey Flower Show

Every year in a field just past the Baker's shop, Stickland's Field, the village flower shop was held. Great competition was had by all the different gardeners around. My father used to win lots of prizes for his fruit and vegetables. Such great care and preparation for good presentation went into it all. We children used to enter the Wild Flower competition to see who could find the most different flowers. We used to walk miles for different kinds, and we used to show them in big stone pickle jars; we got prizes quite often. There was a large marquee with trestle tables all around it for the laying out of the different classes of entry; it was quite a sight. Outside in the field all sorts went on; skittling for a pig, hoopla stalls, lucky dips, and the biggest attraction of all, the Upwey and Broadwey Brass Band. The conductor was a Captain Richards, a smart rosy faced man with white hair and moustache. They wore navy blue suits with wine coloured stripes, and they all looked very smart. They played music from various shows such as" The Merry Widow", together with different military music. It was all very exciting. In the evening they would have dancing, which was not very easy in a field. There was one attraction we all had to watch, Mr Ford would get into a big barrel dressed as an Indian with his face all smothered in brown-

The Circus and the Fair

Sometimes we would have the circus come our way. There were no big Lorries to put the things in, like today, most of the animals had to walk the roads as the circus travelled. We used to walk up Ridgway Hill to meet the caravans, horse-

Towards the fifth of November all the different fairs and show things used to pass by here on the way to Portland Fair. Townsend's Circus used to stop off and show for a few nights in Baker's field in Chapel Lane. Mother washed all the shirts for the Fair workmen, and when it was done we children would take it all back to Mrs Townsend, who lived in a beautiful caravan all glittering with shining mirrors and things. Sometimes she would give us a few free rides on whatever we wanted. We liked the swinging boats and chair-

Children's Fashions

When we went to school there were nowhere near such bright colours in the materials as there are today. We wore coarse materials. Mother made most of my clothes from materials that my elder sisters grew out of, or other people's hand-

A village child's funeral

The first death I remember was when I was about six years old, September 1924. One of our school mates died, Betty Loveless, who lived in Church Street. I remember Mother taking us to see her lying in her coffin; she looked so beautiful, as if she were made of wax. Mother told me to touch her gently on her cheek; how very cold she felt. The day of the funeral all the schoolchildren attended, and about six boys from the school carried the coffin. My brother Valentine was one of them. They wheeled the coffin to the church on a bier. There were ever so many flowers; posies and wreaths of all shapes and sizes. We all filed past the grave; it seemed so deep down in the hole. Most of the grown-

Our Pets

The first dog I can remember was a mongrel called Nell. She was brown and white, a kind of terrier, with rough hair. She was such a gentle dog, and would let us do anything with her. We used to dress her up in doll's clothes and put her in the doll's pram to push around. She would fetch a ball and bring it back to you, sit up and beg for tit-

We had several cats over the years; Muggins was a lovely Tortoiseshell, Tibby a Tabby, and there was a black one, Blackie. Mother kept a goldfinch in a cage hung in the window and once we had a canary. We kept lots of different rabbits over the years, and at one time we had two ferrets. Mr Burden used to keep horses in a field next to us. One was called Kitty, who was very tame and came to the gate for a tit-

Haymaking

Haymaking time was lovely; the horse-

Christmas at Home

At Christmas we went carol singing and Reg Mayo blew his trumpet to accompany us. Sometimes my brother and I would go singing around the houses on our own.

We would take a candle in a jam jar for a light, our hymn books, and go around the big houses. Once we went to sing at the big house opposite the Baker's shop where several sisters, the Misses Saunt, lived. We sang outside the front door and then rang a big clanging bell by pulling a brass handle and then letting it go. Their old maid, Edith Parker, came to the door and would ask us into the drawing room where we had to sing another carol. They would then give us a drink of real lemonade, in hot water, and a mince pie, and as we left they gave us a silver threepenny piece or a sixpence, together with an orange or an apple.

Christmas was a lovely time for us children, we would look forward to it with great excitement. Mother took us to Weymouth to see all the shops trimmed up, and the pretty lights. We also went to see Father Christmas in Bon Marche or some other shop for a lucky dip. We would buy a few presents for each other in Woolworths or the Sixpenny Bazaar, which was a long narrow shop. I think it is Buywise now. At home we made our own trimmings with coloured strips of paper and cold water paste. Mother or the older ones would trim up the room, and Father would buy a Christmas tree, which stood in the corner by the front door. Then there was the thrill of coming down on Christmas morning and seeing the tree all bright with tinsel, candles on clips and various pretty ornaments and parcels. It was lovely. Simple gifts in those days, not as commercial and expensive as it is now. If we children had a box of paints or crayons, a painting book, an apple, an orange, and a few nuts, we were well satisfied.

I once had a little toy shop, and a slate with slate pencils. We hung our little socks up on the bed rail and woke up early to see what Father Christmas had bought us. Then after breakfast we went to Sunday school to thank God for his goodness and all our blessings

AFTER UPWEY

On my fourteenth birthday (31/10/1932) we packed up to leave Upwey, and moved to 54 Chickerell Road, Weymouth. We were all rather sad about this; Mother didn't want to move but it meant that Dad would not have that long cycle ride to Weymouth, where he worked as a Docker.